If 2024 taught me how to embrace loss, 2025 made me realise the necessity of letting go. I wouldn’t say I have mastered the lesson yet to implement it successfully, but I’d like to believe I tried and I’m still trying with every ounce of my being.

There is no comparison that stands when it comes to weighing losses. No scale can tip to make your loss less valid. Pain exists in its own right, just as any of us.

They tell me you are letting your grief overstay its welcome. How do I explain it wasn’t my choice to welcome it in the first place? Worse, when they say you are letting your grief stay longer than he stayed.

My heart sinks. I take a deep breath.

“But you both never even dated.”

My heart silently screams, “But we connected in a way I can’t explain. He understands me in a way no one can. As if we had always known one another…”

I open Instagram and scroll through ‘Fleabag’ reels. I feel seen.

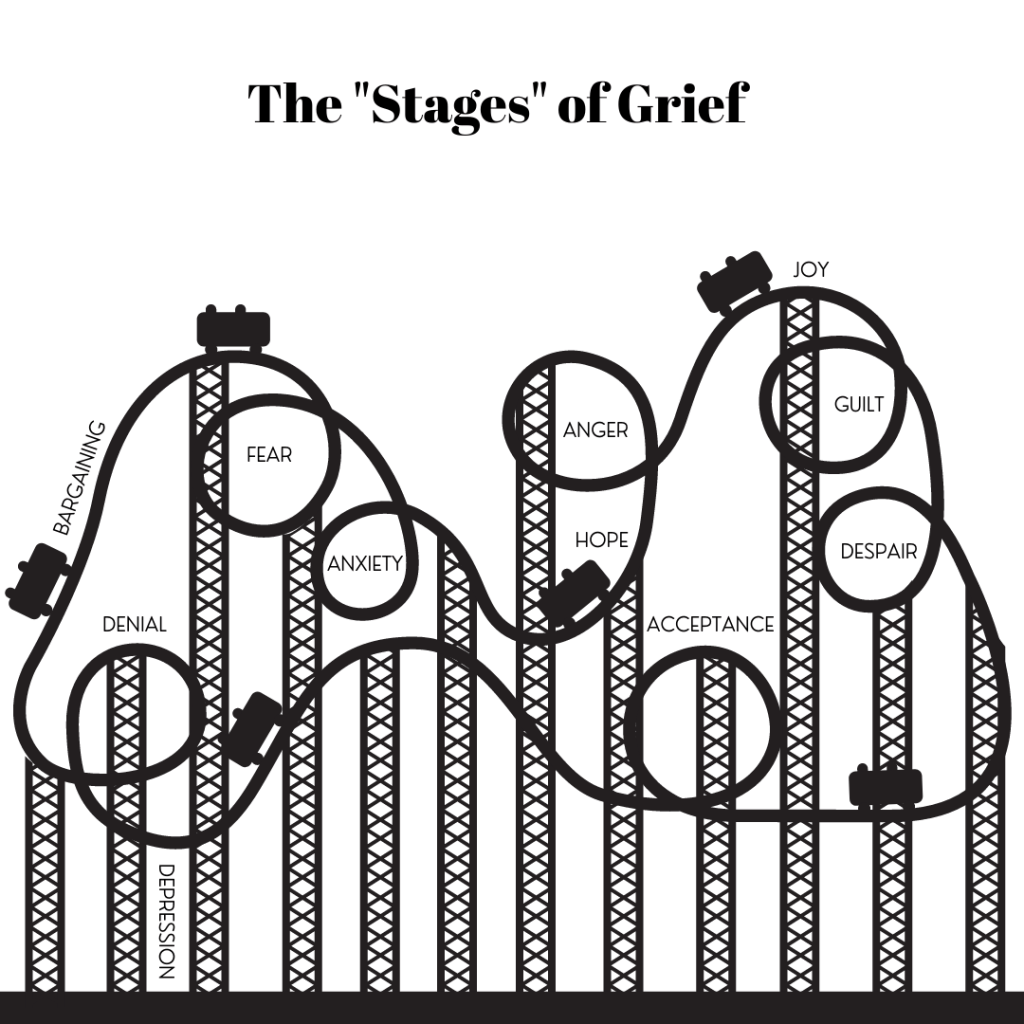

Grief looks different for each one of us, or so I realised this year. Even for the same person, it looks different on different days and different even in different hours of the same day. This year, I realised more than ever how we all are living under a façade. You might be the best-dressed person in a room trying to forget the engulfing bitterness for the evening. But it would not cross anyone’s mind. People are easy to deceive. More so, in this present world of social media. They mistake the highlights for the person’s entire life without giving a second thought to what they may be enduring behind the scenes.

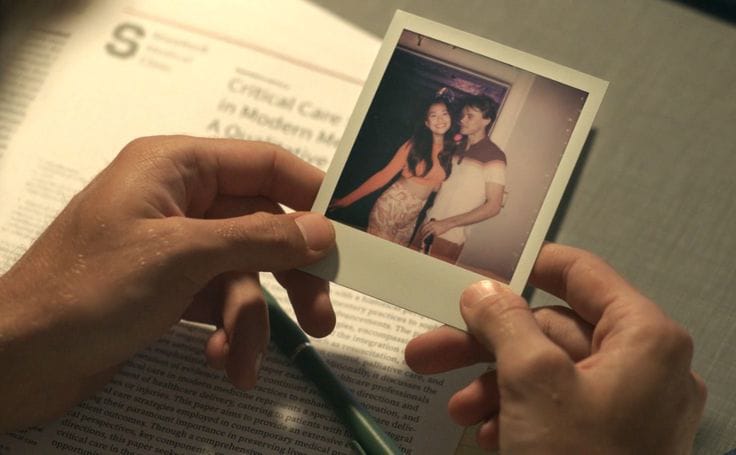

It took my heart months to come to terms with his absence. Like muscle memory, perhaps the heart too has its own kind of reflexes.

Honestly, I wouldn’t even call it a situationship. Perhaps the most beautiful things in life carry no labels. They just simply exist.

I recently read about ‘The Train Theory’ in the caption of an Instagram reel. I quote a line from the post, ‘…two people sharing the same emotional speed for a brief moment without belonging to each other.’ Nothing gave me more solace than reading that short write-up. It seemed as if what I’m going through is probably not that rare. Pain lessens when you know you aren’t alone.

But what makes moving on harder is when you know that none of you actually hate each other. In fact, when the circumstances are to blame, the feelings in most cases are quite the opposite. You can’t help but engage in wishful thinking. Of a reality where the two of you did belong to each other. However, the past weeks made me realise, we in fact did belong to each other in a way perhaps we can never with anyone else. Belonging isn’t always about a happy ending, flowers and butterflies. It’s also about how two people can change each other for the better and evolve as different humans when what they shared comes to an end. While there maybe a ton of unfulfilled wishes and dreams, maybe they came into your life to introduce you to the new dish, the new word, the new place, and maybe a dozen other new(s) that are your bittersweet favourites now.

Some losses are deeply transformative just like the role of the person in your life who you lost. Something shifts inside you, because you know that you now have what you didn’t when you met them. Yet you are stuck in a version of reality that no longer holds true.

But life stops for no one. If they have taught you how to live better, perhaps you know what you owe them.